Well-becoming and waiting lists: UK and Australia

Posted: 10.05.22

IThis month we have two blogs on the topic of waiting lists for planned or elective care. The pandemic has left 1 in 11 of us in the UK on an NHS waiting list. Postponed or cancelled elective surgeries can have a “long shadow” in terms of reducing our ability to work, our ability to undertake caring responsibilities, activities of daily living, and leisure activities. I am delighted to have two Masters by Research students, Jacob Davies, an economist previously working with Welsh Government, and Steve Robson, a consultant surgeon from Canberra in Australia. They are picking up research questions which I started to explore in my own PhD research at the University of York back in 1996.

My Planned Care, Your Planned Care and Our Planned Care in the NHS

Authors: Rhiannon Tudor Edwards and Jacob Davies

In February 2022, the UK Government launched a new ‘My Planned Care’ platform for patients in England to track NHS wating times1. The planned £1.5Bn injection of funds to the NHS to tackle soaring “elective” or “planned care” waiting lists is a result of the back-log of surgery that patients have not had access to during the COVID-19 pandemic2. The latest NHS estimates put current staff vacancies at over 110,0003. Some 70,000 NHS staff were said to be off with illness during April 2022, with COVID-19 related illness said to contribute some 40% (28,000) of that figure4. This inability to recruit the required staff, combined with challenges faced by incumbent staff as they negotiated isolation and social distancing rules in their work, have further attributed to the extensive waiting lists we observe.

Almost all of us know someone in our lives on an NHS waiting list. Waiting lists are the embodiment of “non-price” rationing in public health care systems like the NHS in the UK. They can form a very important purpose if not unacceptably long. They give patients hope and a plan for treatment. They give those with some conditions a chance to get better under a kind of “watch and wait” protocol, and may even give patients time to decide whether they do or do not want surgery after all and would rather medical or lifestyle management going forward. Writing in 1999, Prof. Edwards outlined the need for policies that attempt to tackle NHS waiting lists to address the ‘underlying problem of ensuring that waiting lists operate as an efficient and equitable non-price rationing mechanism’5. Whether the new My Planned Care platform or other policies addressing the COVID-19 induced backlog are successful in achieving this will have to be judged in due course.

A year on an NHS waiting list is very different for each of us, depending on our work and caring responsibilities, pain, anxiety and depression as a result of the condition, and the extent to which it prevents us flourishing in terms of well-being now and well-becoming for the future. Health economists have calculated the “cost” of waiting for different conditions in terms of the expected quality of life gain when patients do get treated, in terms of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). Table 1 below shows some illustrative examples of average QALY gains from six top elective or planned care treatments that patients across the UK are waiting for today and their sources.

Table 1:

Treatment Function |

Average QALY gain of treatment |

Source/Citation |

Trauma and Orthopaedic: |

Cost per QALY of £2128. |

Appleby, Poteliakhoff & Shah et al., 2013 |

Trauma and Orthopaedic |

Cost per QALY of £2101. |

Jenkins, Clement, & Hamilton et al., 2013 |

Ophthalmology: |

Cost per QALY of £1,964. |

SHTAC, Frampton, Harris & Cooper et al., 2014 |

Gynaecology: (Hysterectomy (to combat heavy menstrual bleeding)). |

Cost per QALY of £1600. |

Bhattacharya S, Middleton LJ, Tsourapas A et al., 2011 |

Mental Health |

Cost per QALY of £209 for 6 (sessions) × 30 (minutes) Cost per QALY of £4,453 for 8 × 30 minutes sessions

|

Wu, Li & Parrott et al., 2020 |

Gastroenterology |

Cost per QALY of £1881. |

Cronberg, Appleby & Thompson 2013 |

Published QALY gains are averages, and not everyone put on a waiting list for a cataract operation will have the same level of impaired sight or potential to benefit from that procedure, or will experience the same “health and well-being cost” of having to wait. Chatting to an ophthalmologist, he told us about the “Californian cataract”, which is so mild that it will hardly give any benefit but it still counts in waiting list statistics. Prioritising someone with a very mild cataract just because they have waited a long time, over someone with a very “ripe” or advanced cataract, who has not waited so long, does not make sense, particularly if the latter person is going to receive a noticeably bigger health and well-being benefit for the cost of that operation to the NHS. Pre-pandemic, strict waiting time targets in England were questioned by some surgeons for exactly this reason.

An increasing number of people who previously would not have thought of “going private”, are taking out private health insurance or just paying for a procedure such as a cataract operation (itself around £1,800 per eye). UK protection comparison website ActiveQuote found the number of first-time customers purchasing Private Medical Insurance has doubled since the beginning of the pandemic6. Many of these “going private” are older and very old people who frankly don’t have the time to wait.

Finally, and probably most worryingly, is that a third of all children identified to be needing mental health support are on an NHS or Local Authority waiting list for this care7. Poor mental health in childhood or adolescence has a “long-shadow” in terms of well-being and well-becoming through life.

So, the message is, if, and this is up for debate, but it does align with the underpinning principles of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), we want to get the most health benefits for the population from available funds through the NHS and other care organisations, then we need to at least look at the ball-park cost per QALY estimates of prioritising patients waiting for different elective or planned care procedures. We need to think not only of the surgery itself, but also the pre-and post-operative care and staffing required to deliver this. We need to know where new staff are most needed and to look into localised issues of recruitment and retention, in line with the UK Government’s ‘Levelling-up agenda’. We need to support informal family carers to avoid people coming back into hospital from any complications, and we need to think hard about, across the life-course, who really cannot afford to wait.

In text references:

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/02/nhs-launches-online-platform-to-empower-patients-as-they-wait-for-care/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/news/platform-to-improve-transparency-on-wait-times-and-provide-additional-patient-support

- https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-vacancies-survey/april-2015---december-2021-experimental-statistics

- Chris Hopson, CEO NHS Providers, speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme 14/04/2022. Available here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00168ld

- https://www.bmj.com/content/318/7181/412.full

- https://newsfromwales.co.uk/the-number-of-people-buying-private-healthcare-for-the-first-time-has-doubled-since-covid-19/

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/feb/06/access-to-nhs-mental-health-for-children-remains-a-postcode-lottery

Table 1 references:

- Hip replacement: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3725858/

- Knee replacement: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23307684/

- 2nd eye surgery: http://www.southampton.ac.uk/~gkf1/Presentations/SHTAC%20Second%20eye%20cataract%20surgery.pdf

- Hysterectomy: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99744/

- CBT: https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/publications/the-cost-effectiveness-of-different-formats-for-delivery-of-cogni

- Gastroenterology: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23759893/

Letter from Australia: We need to talk about waiting times and well-becoming

Steve Robson & Rhiannon Tudor Edwards

Waiting lists for elective surgery in Australia have long been a focus of media and political scrutiny. National waiting list data are curated by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) with data released in annual reports. There already were considerable pressures on Australian State and Territory governments to deal with what were perceived as long waiting lists and waiting times for elective surgery. As has been the experience internationally, the COVID-19 pandemic has stressed the Australian health care system at all levels and led to unprecedented delays in patients’ access to planned surgery. The Australian Medical Association (AMA) annual Public Hospital Report Card for 2021 reported:

“Australia’s public hospitals are in crisis. Problems that have existed for years have only been amplified by COVID-19. The situation is even worse when it comes to elective surgery. We continue to see more people being added to the elective surgery waiting lists than are taken off the lists through provision of surgery. As this Public Hospital Report Card shows, during 2020-21 reporting period, for Category 2 elective surgery – procedures like heart valve replacements or coronary artery bypass surgery, one in three patients waited longer than the clinically indicated 90 days, a performance decline of 17 per cent since 2016-17.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed, it is impossible to have a healthy economy without a healthy population. A 2019 paper for the Australian Treasury, Why Health Matters, states the following:

“Economists have increasingly recognised that good health across the whole population significantly contributes to labour and human capital to achieve economic growth. Through higher participation and productivity, good health contributes to economic performance and is positive for individual wellbeing. Good health enables individuals to participate in a range of activities and to engage socially with family and friends and their communities. Good health also allows individuals to be more productive physically and mentally by enabling them to learn more effectively and retain knowledge. Good health also reduces uncertainty, which allows individuals to plan for the whole of life.”

SURGERY IS IMPORTANT FOR HEALTH, WELL-BEING AND WELL-BECOMING THROUGH THE LIFE-COURSE

Surgery plays a fundamental role in healthcare, not only in developed countries but globally. Rose and colleagues have estimated that surgery performed accounts for more than one quarter of all hospital admissions in high-income countries. At a global level, it has been estimated that almost a quarter of a billion major operations are performed each year, and that between 11% and 15% of the global disease burden is amenable to surgical treatment. Disruption to surgery has led to avoidable pain and disability to people who already need treatment to be healthy and productive. An editorial in the British Journal of Surgery made the following observations:

“The ongoing pandemic is having a collateral health effect on delivery of surgical care to millions of patients|…|As regions with the highest volume of operations per capita are being hit, an unprecedented number of operations are being cancelled or deferred. No major stakeholder seems to have considered how a pandemic deprives patients with a surgical condition of resources, with patients disproportionally affected owing to the nature of treatment (use of anaesthesia, operating rooms, protective equipment, physical invasion and need for perioperative care). No recommendations exist regarding how to reopen surgical delivery|…|Patients are being deprived of surgical access, with uncertain loss of function and risk of adverse prognosis as a collateral effect of the pandemic. Surgical services need a contingency plan for maintaining surgical care in an ongoing or post-pandemic phase.”

Not only does delay or cancellation of surgery affect the well-being of patients today, it may have a “long-shadow” in terms of impacting on their health and well-being or well-becoming in subsequent life-course stages. This may be in terms of their mobility, ability to self-care, ability to work, ability to care for others, and enjoyment of recreational activities,

Australia has a health system that is fundamentally different from the UK, NHS-based system. Public hospitals (run by State governments but partially financed by the Federal government) provide free at the point of contact surgery. In Australia, the Federal government provides financial incentives (both cash transfers and tax incentives) for individuals to maintain private health insurance. Usage of the different hospital systems is complex. Waiting lists act as a non-price rationing mechanism in the Australian health care system as in the UK NHS. A recent but pre-pandemic study found that, despite having private health insurance, 40% of people receive inpatient services exclusively in public hospitals. Only 62% of overnight hospital admissions were claimed on private health insurance. 66% of people receive services in public hospitals for surgical admissions.

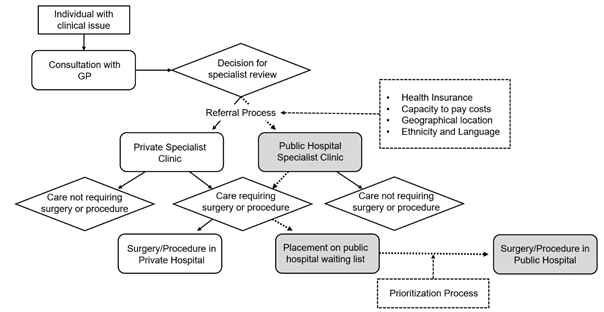

Waiting lists for Australian public hospitals are prioritized according to an agreed system with national targets for surgical access. All referrals for surgical care originate with general practitioners (GPs) in Australia, and the process for patients being referred for care in public or private hospitals is managed by those GPs as shown in the flow diagram below:

Flow diagram 1. Referral process for elective care in the Australian health care system

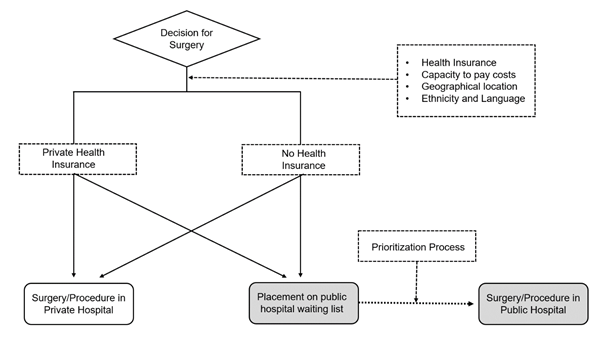

Once a patient has seen a surgeon and been listed for surgery, there is some choice in the way this is performed, with some patients who do not hold private health insurance opting to pay the overall costs for surgery in a private hospital. The flow diagram is shown below:

Flow diagram 2. Choice options for patients in the Australian health care system seeking surgery

The system was at capacity before the pandemic: AIHW data reported that, during the financial year 2017–18, there were 11.3 million episodes of admitted patient care in Australia’s public and private hospitals: 60% of these occurred in public hospitals. Private hospitals accounted 59% of surgical episodes of admitted patient care and of the 2.3 million episodes of admitted patient care involving elective surgery, 34% were in public hospitals and 66% in private hospitals.

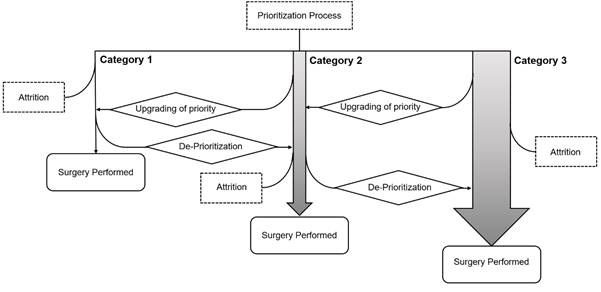

As in the UK, Australia now has to deal not only with the background inflow of patients to waiting lists for planned surgery, but with an enormous backlog of patients who have been unable to access surgery during the pandemic – many of whom have experienced deteriorations in their clinical condition due to the delays. The pre-pandemic algorithm for public hospital waiting lists in Australia was like this:

Algorithm 1. Waiting list prioritization algorithm pre-pandemic

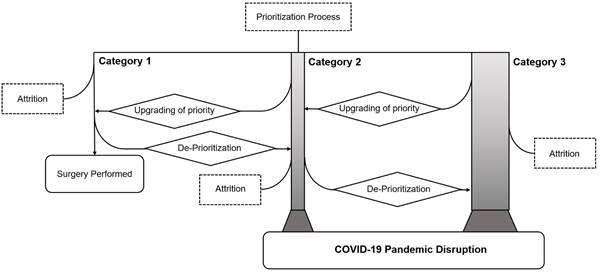

… but now looks like this:

Algorithm 2. Waiting list prioritization algorithm post-pandemic

Globally, a number of groups have reported descriptions of new models for prioritization of surgical patients who languish on lengthy waiting lists. How generalizable these new tools are remains to be seen.

RETHINKING PRIORITIES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF WAITING LISTS TO SUPPORT PATIENT HEALTH, WELL-BEING AND WELL-BECOMING

In most democratic countries an important principle of providing health care is equity. Horizontal equity refers to the situation in which all people are treated equally – that those with similar needs are provided similar treatment irrespective of their capacity to pay. This was one of the founding principles of the Beveridge Plan in 1942, which led to the establishment of the NHS in 1948. Vertical equity refers to ‘unequal treatment of unequals’, where people with greater means contribute a higher proportion of the costs of care. With Australia’s parallel systems of public and private health care, how can equity be applied when dealing with waiting lists that have ballooned during the pandemic? There are important consequences of waiting list management: “Waiting times have been shown to be associated with patient dissatisfaction, delayed access to treatments, poorer clinical outcomes, increased costs, inequality, and patient anxiety.”

Ongoing research at the Centre for Health Economics and Medicines Evaluation (CHEME) by Steve Robson and Professor Rhiannon Tudor Edwards will explore the issue of waiting list management in Australia from multiple perspectives. These perspectives span:

- Who is being referred for surgical care and are there systematic differences in referral patterns?

- Are there systematic biases in access to surgery according to factors such as socioeconomic status?

- How large a part does geography play in access to surgery?

- Are there systematic differences in access to high- and low-value surgical procedures, where value refers to cost per QALY or cost per DALY?

- What QALY gains can be made with different approaches to surgery prioritization?

The opportunity to compare surgical access across the UK and Australian systems promises to be interesting.