The Well-becoming of all: Levelling Up and mitigating the Inverse Care Law

Kalpa Pisavadia, Abraham Makanjuola, Jacob Davies, Llinos Haf Spencer, Annie Hendry and Rhiannon Tudor Edwards.

Posted: 05.08.22

Well-becoming is a focus on health and well-being throughout the life course, and this is something that can benefit all of us when considering the link between poor health and poverty. For example, life expectancy is almost eight years shorter in Blackpool than in Guildford, with a similar gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest women across the UK (Mason, 2022). In the most deprived areas of Wales, between 2018 to 2020, life expectancy at birth for males was 74.1 years, and 78.4 years for females. Life expectancy in the least deprived areas was 81.6 years and 84.7 years, respectively (Wales - Office for National Statistics, 2022). Not only are the poorest people in the UK living shorter lives, but they are also living with poorer health. From 2018 to 2020, females in Wales’s most deprived areas were expected to live more than a third of their lives with activity-limiting illnesses (Wales - Office for National Statistics, 2022). This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic in which housing, employment, education, and the environment among communities with high levels of multiple deprivation have significantly suffered (Griffith et al, 2020; Wolfson and Leung, 2020). A recent quasi-experimental study measuring years of life lost (YLL) associated with the pandemic in England and Wales concluded that the most deprived regions with long-standing health inequalities reported the highest numbers of potential YLL (Kontopantelis et al., 2022). Thus, we can surmise that there is a connection between poor health and poverty.

Geographical deprivation has long been an issue in the UK which was addressed by the Welsh general practitioner Julian Tudor Hart in 1971 when he published the ‘Inverse Care Law’ in The Lancet Journal (Tudor Hart, 1971). This influential paper voiced the views that formed the foundation of the National Health Service. The ‘Inverse Care Law’ drew attention to the unfairness within the distribution of health and social care services. For example, those in greater need of health services are least likely to receive it, such as those in deprived areas where General Practitioner (GP) services are lacking. However, those living in more affluent areas tend to have a better quality of services and much greater access than their counterpart (Appleby and Deeming, 2001).

Building on what Dr Hart had highlighted, Shaw and Dorling introduced the Positive Care Law, which states that in deprived areas where health care is most needed yet has the least provision, informal care, such as unpaid carers, is at its greatest (Shaw and Dorling, 2004). Tudor Hart supported the Positive Care Law stating in an editorial to the British Journal of General Practice that the Positive Care Law is an example of market failure, covered up by benevolent acts of people in the local community (Tudor Hart, 1971). Although the Positive Care Law does make it difficult to gauge the level of unmet need in an area, many people perceive that where they live affects the quality of service they receive (Shaw and Dorling, 2004; Nuffield Health, 2022). There does seem to be a marginal difference in the average waiting times across NHS services between the North and South of England. The average waiting time across NHS services in London and the Southwest of England is 10.8 weeks and 12.9 weeks, respectively. Whereas waiting times in the Midlands and the East of England average 14.1 weeks and 13.3, respectively, across services (NHS England, 2022). However, the Positive Care Law creates challenges in deciphering exactly where funds and resources are needed (Shaw and Dorling, 2004).

Vulnerable populations with protected characteristics

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has made us acutely aware of inequalities, many of these predated the pandemic. The Inverse Care Law has always had implications for healthcare for vulnerable populations with protected characteristics, such as low-income persons and ethnic minorities. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many communities sharing common protected characteristics such as race, disability, geography, and gender, were already experiencing high levels of multiple deprivation (Iacobucci, 2020). Protected characteristics are often a precursor to unmet needs within health and social care. For example, a cross-sectional study based in the USA found that individuals dealing with more impairments and individuals from marginalised groups reported more unmet needs than their counterparts (Hunt and Adams, 2021). This study indicated that various personal identity and social factors were associated with perceiving an unmet treatment need, including age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, marital status, and poverty level. Individuals from minority and socially marginalised groups who had experienced a mental depressive episode and had a history of co-occurring substance use disorders reported unmet treatment needs at higher rates than their counterparts.

Notably, the pandemic has revealed the ways in which race and culture play a role in whether certain groups access care (Raleigh & Holmes, 2021). In the UK, it is well documented that the communities that suffered the most from COVID-19, for example, ethnic minority communities, are now those with the lowest vaccination uptake rates (Kamal, et al, 2021). The early outbreak of COVID-19 in the UK was concentrated in densely populated urban areas with predominantly larger groups of ethnic minorities, such as London. As of early May, there were higher levels of hospitalisation among ethnic minorities due to COVID-19 in the northwest of England, particularly in the urban areas of Manchester and Liverpool (Verhagen et al., 2020). A retrospective cohort study conducted using the Greater Manchester Care Record found that ethnic inequalities in vaccine uptake were wider for COVID-19 than for influenza, suggesting that the COVID-19 vaccination programme has created additional inequalities (Watkinson et al, 2022). The identification of social vulnerability in a US-based study allows us to surmise indicators in identifying the most at-risk populations in the UK. This study found that black people in America are at a disproportionately higher risk of death from COVID-19 than other racial groups (Gaynor and Wilson, 2020).

The evidence is limited as to why ethnic minorities are turning down COVID-19 vaccinations in the UK and the USA. A rapid evidence summary conducted in 2021 for the Wales Covid-19 Evidence Centre found that mistrust of public health agencies was a barrier to vaccination uptake within ethnic minority communities partly due to past experiences of stigmatisation, discrimination, and racism (Okolie, 2021). There are some parallels to these findings with mental health systems in the USA, in which racism has been found to be a main cause of mistrust, resulting in untreated mental health conditions (Alang, 2019). Although further research is needed, policy action is pertinent in understanding the barriers to vaccine uptake and building trust amongst minority ethnic communities. Some innovative solutions did arise during the pandemic to tackle this issue. For example, OneNorwich Practices Ltd. (ONP) became a key player during the pandemic by setting up mobile vaccination clinics in mosques, hostels and homeless settings (NHS UK, 2021). Through this initiative, ONP was able to reach ethnic minority people, many of whom were not registered with a GP (Hewitt, 2022). However, there is a need for anti-racism education for healthcare professionals to reduce unmet needs within ethnic minority communities (Alang, 2019).

The Levelling Up strategy

As the Inverse Care Law is as applicable to the wider determinants of health as it is to the distribution of health services, alleviating pressures on health resources can be achieved with innovative solutions for economic prosperity and growth. In their 2019 manifesto, the Conservative Party introduced the concept of ‘Levelling Up’ with an agenda to improve economic dynamism and innovation in deprived areas (The Conservative and Unionist Party, 2019). Economic growth and higher productivity have been concentrated in specific areas, most notably the South of England, exacerbating the North-South divide in terms of job opportunities, salary, education and widening health inequalities among the population (Tomaney & Pike, 2020). Levelling up focuses on wider determinants of health and geographical inequality with the aim to drive growth by increasing jobs and opportunities in the private sector and improving public services such as education, transport, and recreational facilities in deprived areas (GOV.UK, 2022).

The Levelling Up strategy does make some effort to alleviate the Inverse Care Law within certain areas. In towns across the UK, such as Lincolnshire, Margate and Corby, the funds have been spent on urban greening, public transport, housing, tourism schemes, the creative arts and education, creating many employment opportunities (Towns Fund, 2020). However, it is questionable whether the £2.4bn investment in the Towns Fund of the Levelling Up strategy reaches the most deprived areas. Counsellors are asked to bid competitively against each other for the funding, creating a subjective analysis of where money needs to go rather than which area is most in need (Mason, 2022). So why are not the most deprived areas winning bids for funding? A recent panorama documentary accused the Levelling Up secretary Michael Gove of pork-barrel politics, questioning why 80 of the 101 areas due to receive a proportion of the £3.6bn of the Towns Fund were represented by Conservative MP’s. It is also worth noting that only 38% of councils won some of the Levelling Up Fund money they requested, 34% did not participate, and 28% had all their bids rejected (Mason, 2022).

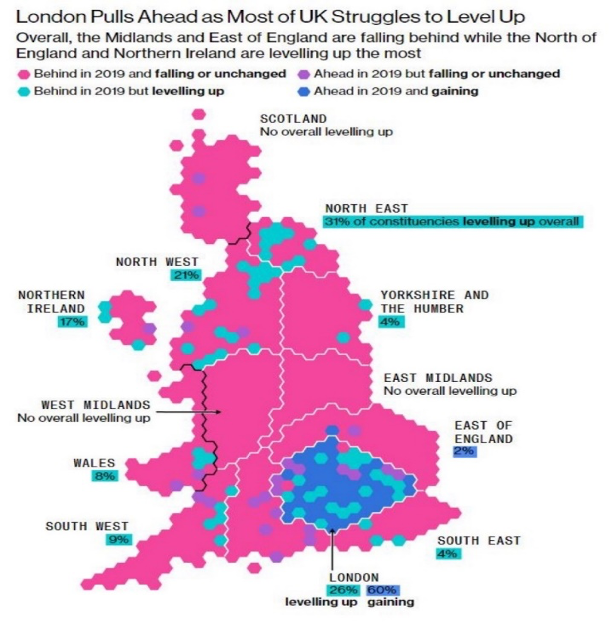

The below infographic shows that most of the UK has fallen further behind London and the Southeast since Boris Johnson became Prime Minister, with no overall Levelling Up in the Midlands.

(Mayes et al., 2022) https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/uk-levelling-up/boris-johnson-level-up-plan-in-trouble.html

The Levelling Up strategy is a commendable idea; however, the strategy must ensure that people in deprived areas have the same quality of life as those in more affluent areas. Improving infrastructure and giving newly graduated and talented young people a reason to stay rather than seek opportunities in more affluent areas is a practical way of preventing disparities between regions and, by extension, health inequalities (Britton, et al, 2021). Mitigating disparities in opportunities can only be achieved with a fairer funding distribution system. For example, the Wales Economic Action Plan, Prosperity for All, has developed a regional model of economic development to help drive opportunities in every part of Wales with the aim to maximise opportunities wherever people live, which will pave the way in alleviating regional inequalities (Welsh Government, 2017).

Innovative solutions for mitigating the Inverse Care Law

It is important to recognise the vast volunteer sector in the UK that has been working on alleviating poverty, social exclusion, and other wider determinants of health for decades. In Wales, the emergence of various social enterprises has shown us that plenty more can be done to lessen inequalities by fostering innovation in low-income, rural areas. These enterprises address local issues and health determinants to provide more sustainable and resilient community-based health and social care provision. Investors in Carers (IiC) is a framework to raise awareness and provide credit for good practice and support services provided to carers by General Practices. The scheme has helped identify over 100 carers who were not receiving carer allowances. The main benefits for carers from the scheme included improved choice and access to services, signposting to respite care, and recognition of carer contribution (Best and Myers, 2019).

Similarly, an enterprise in St Helen’s, The Capable Coping Project, aimed to build self-help and community action capacity. The enterprise achieved this by establishing Volunteer Village Wardens (VVWs), whose role was to assist in social care activities and a Dawn Patrol Scheme, which encouraged schoolchildren to check daily on the welfare of older and vulnerable residents (Best and Myers, 2019). Although this element of the Dawn patrol scheme worked better in urban rather than rural areas due to the greater distance between dwellings, the scheme also provided improved security and safety for people living alone, particularly older people, with the aim to reduce the isolation they suffer (The National Lottery Community Fund, 2022). VVWs were well received by local communities and received around six new referrals a month, with an average of seven visits per person. The most sought-after services included: accessing local amenities, companionship, transport, and help with completing forms (Best and Myers, 2019).

Successful social enterprises and the volunteer sector can tell us much about where funding can be distributed and be the most effective. The Social Value Hub at the Centre for Health Economics and Medicines Evaluation offers support, advice, training, and consultancy to organisations that offer social prescribing programmes, such as lifestyle coaching, or outdoor activities such as gardening, sports or green crafts. Researchers at the Social Value Hub measure and communicate the positive changes that social enterprises are creating for people and the environment (CHEME, 2022). The social prescribing initiatives that are evaluated are third-sector driven, volunteer-focused and non-clinical approaches to addressing health and well-being among the population. For example, one of the social prescribing programmes currently being evaluated is a community-based service called TRIO, provided by Person Shaped Support (PSS) (Person Shaped Support, 2022). With the aim to keep people connected with their local community, a person living with dementia is matched with a TRIO companion who provides regular, weekly support for up to three people living with dementia who share similar interests (Health and Care Economics Cymru, 2022). The economic evaluations conducted by researchers at the Social Value Hub use Social Return on Investment methodology, which includes a mixture of qualitative and quantitative evidence to provide a robust analysis of the social change that programmes such as TRIO have created (CHEME, 2022). This type of analysis has shown that investing in the volunteer sector has the potential to alleviate pressures on the NHS.

Decision-making on the well-becoming of all depends on our social and political environment. It is imperative that we level up to improve the living standards for all, but this must be achieved with a fair system of distributing the available funding. Building trust amongst hard-to-reach communities is equally important in ensuring that the most vulnerable populations receive and access the care they need. The pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated existing inequalities, and there is much to be learned from innovative solutions that both predated the pandemic as well as came to be a result of it. What social enterprises can teach us is that communities and organisations can facilitate the reduction of social inequalities by encouraging people to take action and strive toward a fairer society and even distribution of welfare.

References

Alang, S. M. (2019). Mental health care among blacks in America: Confronting racism and constructing solutions. Health Services Research, 54(2), 346. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13115

Appleby, J., & Deeming, C. (2001). Inverse care law | The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/inverse-care-law

Best, S., & Myers, J. (2019). Prudence or speed: Health and social care innovation in rural Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 70, 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRURSTUD.2017.12.004

CHEME. (2022). CHEME Social Value Hub | Bangor University. https://cheme.bangor.ac.uk/social-value-hub/index.php.en

GOV.UK. (2022). Levelling Up the United Kingdom - GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom

Griffith, D. M., Sharma, G., Holliday, C. S., Enyia, O. K., Valliere, M., Semlow, A. R., Stewart, E. C., & Blumenthal, R. S. (2020). Men and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial approach to understanding sex differences in mortality and recommendations for practice and policy interventions. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. https://doi.org/10.5888/PCD17.200247

Health and Care Economics Cymru. (2022). Short breaks for people living with dementia and their carers: exploring wellbeing outcomes and informing future practice development through a Social Return on Investment approach. https://healthandcareeconomics.cymru/short-breaks-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-exploring-wellbeing-outcomes-and-informing-future-practice-development-through-a-social-return-on-investment-approach/

Hewitt, P. (2022). Fitter, healthier, happier: Rebuilding the nation’s health after COVID-19 - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuFavb86reY&list=PLn2ishLipkeHcv2v1jUbOaBrhHnYPdh3G&index=55

Hunt, A. D., & Adams, L. M. (2021). Perception of Unmet Need after Seeking Treatment for a Past Year Major Depressive Episode: Results from the 2018 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 92(3), 1271–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11126-021-09913-Y

Iacobucci, G. (2020). Public health priorities for 2020. BMJ, 368, m31. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.M31

Kamal, A., Hodson, A., & Pearce, J. M. (2021). A Rapid Systematic Review of Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake in Minority Ethnic Groups in the UK. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101121

Kontopantelis, E., Mamas, M. A., Webb, R. T., Castro, A., Rutter, M. K., Gale, C. P., Ashcroft, D. M., Pierce, M., Abel, K. M., Price, G., Faivre-Finn, C., van Spall, H. G. C., Graham, M. M., Morciano, M., Martin, G. P., Sutton, M., & Doran, T. (2022). Excess years of life lost to COVID-19 and other causes of death by sex, neighbourhood deprivation, and region in England and Wales during 2020: A registry-based study. PLOS Medicine, 19(2), e1003904. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1003904

Mason, C. (2022). BBC iPlayer - Panorama - Fixing Unfair Britain: Can Levelling Up Deliver? https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0015fnh/panorama-fixing-unfair-britain-can-levelling-up-deliver

Mayes, J., Tartar, A., & Demetrios, P. (2022). Cost of Living Crisis, House Prices, Universal Credit: Most of UK Is Not ’Levelling Up’. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/uk-levelling-up/boris-johnson-level-up-plan-in-trouble.html

NHS England. (2022). Statistics » Consultant-led Referral to Treatment Waiting Times Data 2021-22. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/rtt-waiting-times/rtt-data-2021-22/#Dec21

NHS UK. (2021). OneNorwich Practices | Covid-19 vaccinations. https://onenorwichpractices.nhs.uk/our-work1/covid-19-vaccinations

Nuffield Health, P. P. P. (2022). Fitter, healthier, happier: Rebuilding the nation’s health after COVID-19 - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuFavb86reY&list=PLn2ishLipkeHcv2v1jUbOaBrhHnYPdh3G&index=54

Okolie, C. (2021). Wales COVID-19 Evidence Centre (WC19EC) Rapid Evidence Summary. https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/observatory/evidence/evidence-documents/res-00006-wales-covid-19-evidence-centre-rapid-evidence-summary-vaccine-uptake-equity-june-2021-9-7-21-pdf/

Person Shaped Support. (2022). TRIO | PSS. https://psspeople.com/help-for-professionals/social-care/trio

Raleigh, V., & Holmes, J. (2021, September 17). The health of people from ethnic minority groups in England. The Kings Fund ; Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1111/DME.13895

Shaw, M., & Dorling, D. (2004a). Who cares in England and Wales? The Positive Care Law: cross-sectional study. British Journal of General Practice, 899.

Shaw, M., & Dorling, D. (2004b). Who cares in England and Wales? The Positive Care Law: cross-sectional study. The British Journal of General Practice, 54(509), 899.

The Conservative and Unionist Party. (2019). Conservative Party Manifesto 2019. https://www.conservatives.com/our-plan/conservative-party-manifesto-2019

The National Lottery Community Fund. (2022). Dawn Patrol Scheme - Project. https://www.tnlcommunityfund.org.uk/funding/grants/0030138702?msclkid=e6ab1410d13e11eca303066ca04f95b0

Tomaney, J., & Pike, A. (2020). Levelling Up? The Political Quarterly, 91(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12834

Towns Fund. (2020). Towns Fund: Levelling Up in Action — townsfund.org.uk. https://townsfund.org.uk/blog-collection/towns-fund-levelling-up-in-action

Tudor Hart, J. (1971). THE INVERSE CARE LAW. The Lancet, 297(7696), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X

Verhagen, M. D., Brazel, D. M., Dowd, J. B., Kashnitsky, I., Kashnitsky, I., & Mills, M. C. (2020). Forecasting spatial, socioeconomic and demographic variation in COVID-19 health care demand in England and Wales. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12916-020-01646-2/FIGURES/8

Wales - Office for National Statistics. (2022). Health state life expectancies by national deprivation quintiles, Wales - Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/bulletins/healthstatelifeexpectanciesbynationaldeprivationdecileswales/2018to2020

Watkinson Id, R. E., Williams Id, R., Gillibrand, S., Id, C. S., & Id, M. S. (2022). Ethnic inequalities in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and comparison to seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in Greater Manchester, UK: A cohort study. PLOS Medicine, 19(3), e1003932. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1003932

Welsh Government. (2017). Regional Investment in Wales After Brexit: Securing Wales’ Future. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-10/regional-investment-in-wales-after-brexit.pdf

Wolfson, J. A., & Leung, C. W. (2020). An Opportunity to Emphasize Equity, Social Determinants, and Prevention in Primary Care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 18(4), 290–291. https://doi.org/10.1370/AFM.2559