Well-Becoming Wales: Health Economics and the Choices Ahead Post-Pandemic

Rhiannon Tudor Edwards

Posted: 11.02.22

This is the first in a series of post-pandemic blogs on the application of health economics research into "well-becoming". We hear a great deal about well-being now but not so much about "well-becoming". There are various definitions of well-being. The Oxford English dictionary defines well-being as the state of being or doing well in life, and being comfortable, healthy and happy (OED, n.d.). Behavioural economics and behavioural psychology researchers have explored what we mean by happiness (Layard, 2020). I like Paul Dolan's definition of happiness as "happiness in an experience with purpose" (Dolan, 2014). I like to think of well-becoming as the experience of flow or change over the life-course. I have only seen two uses of this term “well-becoming”. The first has emerged out of the capability measure development programme (Mitchell et al., 2021) and in education research in the distinction between children as “being” and “becoming” in the world (Cassidy & Mohr Lone, 2020). A well-becoming “lens” means that when we are evaluating any intervention in terms of it costs and benefits now, we are also thinking about how it affects health and well-being in subsequent stages of life. Woven through this is how we determine, shape, and set ourselves up in future stages of life.

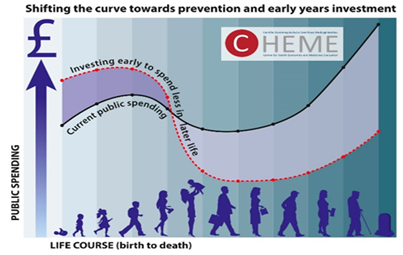

This is almost a counter-factual argument regarding what we know at a population level. We know that children who have grown up in poverty or have been exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACES) may not make good life decisions and have poorer physical and mental health later in life (Hughes et al., 2017). Access to higher education is much lower for young people who have been in care. In 2018-19 only 13 percent of pupils who were looked after continuously for 12 months or more entered higher education compared to 43 percent of all other pupils (Office for Students, 2022). Below is an image that will be familiar to those who know me, emphasising prevention over cure through the life-course.

Source: Edwards et al. (2016)

Health economics is the study of how we use scarce health care and increasingly social care resources to meet our needs (Drummond et al., 2015). Over my 30-year career as an academic health economist, my observation has been that we increasingly need to take a wider perspective in our research to inform evidence-based government policy. Over the last 150 years, arguably the most significant advances in life expectancy have come from public health, spanning improvements in sanitation, clean water, housing, work conditions and education. Applying health economics to the evaluation of public health interventions throws up many additional challenges today. Evaluating interventions to support behaviour change, such as encouraging people to stop smoking, eat healthily and exercise, require pragmatic research designs that cannot always be in the form of gold-standard randomised controlled trials. The precautionary principle, which has been used so much to make policy at speed through the pandemic, is perhaps more relevant here. This combines gold-standard evidence with more pragmatic and counter-factual evidence based on our prior beliefs, lived experience and stakeholder voice, and is updated when new evidence becomes available (Edwards & McIntosh 2019; Fischer & Ghelardi, 2016; Rose, 2008).

So, what are two pressing "well-becoming" choices faced in Wales as we come out of the pandemic? First, we face choices about spending public money on children and young people and their education. This is against the backdrop of new "Children's rights" legislation, and in this, Wales is leading the way. Where does investment really make the biggest difference, particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged children and young people from 0-18 years? There are lots and lots of health economists around now working in academia, at the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and in the pharmaceutical industry. There are far fewer education economists and there is far less published literature on the value for money or cost-effectiveness of interventions or policies in education. In Wales, education is a major budget area, second to health care spending. Yet even though much spending is underpinned by legislation, we know very little about the "value for money" to the public purse of investing in different areas of the early life-course (Edwards et al., 2016).

A second post-pandemic choice relating to well-becoming later in life is how to prioritise and fund initiatives to reduce the NHS waiting lists for “elective” or “planned care” that has built up through the pandemic. Waiting times for routine and highly beneficial and cost-effective interventions such as cataract removal are now as long as three years. We could use cost per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) evidence to help frame strategies to prioritise some procedures. We could be more explicit about prioritising people for whom being on a waiting list means they cannot easily continue their caring responsibilities, keep working, and for whom pain or mental health issues are making life more difficult. I studied this topic for my PhD over 30 years ago (Edwards, 1999). I am pleased to have postgraduate students looking at this topic again post-pandemic. Access to elective or planned care to remove a cataract, replace a hip or provide counselling can help people into their next stage in life, promoting independence and resilience. The well-becoming argument looks critically at how we address and finance the waiting list backlog now that we are post-pandemic. For me, the most concerning waiting lists are those for mental health services for children and young people, a third of whom are having to wait long periods for help (Local Government Association, 2022). Those of us working in public health economics have long been bemused by the need for public health interventions to demonstrate saving and return on investment (ROI). It is time to look at the routine elective or planned procedures and apply the same measuring rod from a societal perspective. There is a danger that an agism argument can creep in, so emphasis needs to be on capturing benefits to the patient and their informal carers, whatever stage of life a patient may be in.

This is the first of a series of blogs framing the health economics research that I am doing with colleagues at the Centre for Health Economics and Medicines Evaluation (CHEME) with a well-becoming lens. In the next blog I describe a study led by University College London about support groups for people caring for family members with rare dementias. Well-becoming is not all about children and young people. In this case it is about the role of caring later in life.

References

Cassidy, C., & Mohr Lone, J. (2020). Thinking about childhood: Being and becoming in the world. Analytic Teaching and Philosophical Praxis, 40(1), 16-26.

Dolan, P. (2014). Happiness by design: change what you do, not how you think. Hudson Street Press.

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G. L., & Torrance, G. W. (2015). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford university press.

Edwards, R.T. (1999). Points for pain: waiting list priority scoring systems. BMJ, 318(7181), 412-414. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.318.7181.412.

Edwards, R. T., Bryning, L., & Lloyd-Williams, H. (2016). Transforming young lives across Wales: The economic argument for investing in early years. Bangor, UK: Bangor University. https://cheme.bangor.ac.uk/documents/transforming-young-lives/CHEME%20transforming%20Young%20Lives%20Full%20Report%20Eng%20WEB%202.pdf

Edwards, R.T., & McIntosh, E. (2019). Applied Health Economics for Public Health Practice and Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fischer, A. J., & Ghelardi, G. (2016). The precautionary principle, evidence-based medicine, and decision theory in public health evaluation. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 107.

Hughes, K., Bellis, M.A., Hardcastle, K.A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M.P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), pp.e356-e366.

Layard, R. (2020). Richard Layard on Happiness Economics. from https://www.socialsciencespace.com/2020/02/richard-layard-on-happiness-economics/

Local Government Association. (2022). Children and young people’s emotional wellbeing and mental health – facts and figures | Local Government Association. https://www.local.gov.uk/about/campaigns/bright-futures/bright-futures-camhs/child-and-adolescent-mental-health-and

Mitchell, P. M., Husbands, S., Byford, S., Kinghorn, P., Bailey, C., Peters, T. J., & Coast, J. (2021). Challenges in developing capability measures for children and young people for use in the economic evaluation of health and care interventions. Health Economics.

OED: Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). The definitive record of the English language. https://www.oed.com/oed2/00282689

Office for Students. (2022). Care experienced students and looked after children. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/effective-practice/care-experienced/

Rose, G.A., Khaw, K.T., & Marmot, M. (2008). Rose's strategy of preventive medicine: the complete original text. Oxford University Press.