“Small is Beautiful” as the principle for recognising and mitigating economic and population health challenges of climate change here in Wales

Posted: 16.02.24

By Edwards R. T., Pisavadia, K. and Roberts, S.

Wales is a small and beautiful country. The phrase “Small is Beautiful” is the title of a book written by German economist Ernst Schumacher, published in 1973. Schumacher was the protégé of British economist John Maynard Keynes. In the UK, Schumacher was interned during World War II and released with the help of Keynes. Through Schumacher’s farsighted thinking, he contributed to Britain's post-war economic recovery. Fifty years on, his book “Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered” has much to offer in guiding the way we address climate change and the economic challenges facing us here in Wales post-COVID-19 pandemic, post-Brexit, and as a result of the war in Ukraine. Along with Schumacher’s book, two other books have informed this blog: “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st-Century Economist” by Kate Raworth (2017) and hot off the press “Escape from Overshoot: Economics for a Planet in Peril” by Peter Victor (2023). Doughnut economics is a framework for sustainable development, shaped like a doughnut or lifebelt. It combines the concept of planetary boundaries with the complementary concept of social boundaries. Raworth argues that it is imperative that we remain within the bounds of producing enough necessary goods and services to meet the population’s essential needs without depleting vital natural resources (Raworth, 2017). “Escape from Overshoot” is a book that extends the concept of “economic growth” breaking planetary boundaries and stretching inequality and injustice (Victor, 2023).

Schumacher (1973) took several themes in his book. First, the dangers of treating the natural environment as a source of income rather than as capital, not to be squandered; second, economic reasons for war and conditions for peace, which seem very relevant at the moment with conflict in Ukraine and Palestine; third, the short-sightedness of opting for nuclear energy as a “clean source of energy” but with an unknown burden of the disposal of nuclear waste on future generations; and fourth, economic development and the role of “intermediate technologies” in producing good work for a population. The agenda for net zero and increased recognition of the local and global impacts of climate change make much of what Schumacher wrote over fifty years ago very salient today.

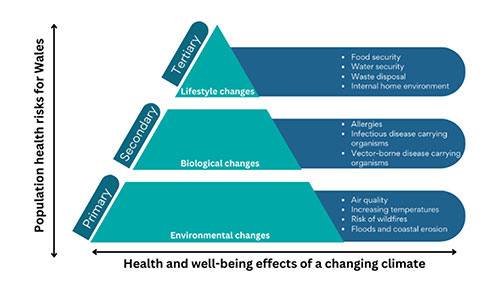

Here, we have divided the direct localised threats of a changing climate to population health into three groups:

- Those that affect our natural environment (changes in air quality, increasing temperatures, more risk of fires, floods and coastal erosion).

- Those that affect the way we live (food and water security, waste disposal, and our internal home environments).

- Those that affect us through biological changes (prevalence of infectious or vector-borne disease carrying organisms such as mosquitos).

These threats come from a recent analysis by the UK Health Security Agency (2024). For humans to thrive very much depends on the planet thriving. This means that we need nutrient rich soils to grow sufficient and nutritious food. We need ample fresh water to regenerate our rivers and aquifers and clean air to breathe, which means considerably reducing emissions (Raworth, 2017).

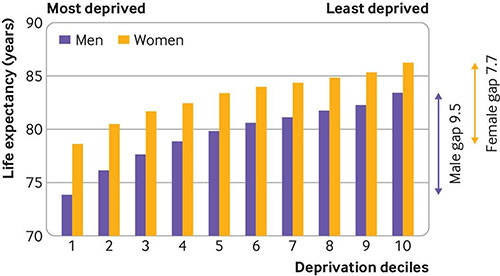

The underpinning relationship of concern should, however, be the relationship between climate change at a local level and the socio-economic gradient of ill-health, disability and premature mortality. The well-established Marmot curve shows the relationship between the neighbourhood in which we live and our quality-adjusted life expectancy (see Figure 1 below; Marmot, 2020).

Figure 1: Life expectancy at birth by area deprivation deciles and sex, England, 2016–18. Based on data from Public Health England, 2020 (Marmot, 2020).

*There is an accessible version of this graph is below.

Deprivation Decile from most to least deprived |

Life expectancy for Men |

Life expectancy for women |

1 |

73.9 |

78.6 |

2 |

76 |

80.5 |

3 |

77 |

81.5 |

4 |

79 |

82.5 |

5 |

79.9 |

84 |

6 |

80.3 |

84.5 |

7 |

81 |

84.7 |

8 |

81.5 |

84.9 |

9 |

82 |

85.3 |

10 |

83.4 |

86.3 |

Wales is one of the poorest regions of the UK. At a local level, Wales has some of the very poorest urban and rural communities seen in the UK. One in three children growing up in Wales are living in poverty (Roberts et al., 2023). The ageing nature of the population of Wales, through, in part, retired incomers, means that there is an insufficient working age population to support this demographic pattern.

Schumacher (1973) focused on the quality of work that people have in an economy. He wrote mainly about developing countries, but his ideas are relevant to developed countries such as the UK. He argued for local work of good quality rather than neo-colonial work of poor quality. It is hard to view global conglomerate employers, recently expanding business in Wales and offering variable or zero-hours contracts, as the type of employers that Schumacher envisaged. Conglomerate employers follow the same trajectory foregrounded in the Industrial Revolution, which focuses primarily on capital and labour. Economic thought needs to pay more attention to the ecological stresses that large global firms put on the planet such as, climate change, deforestation and soil degradation (Raworth, 2017).

Again, in the context of developing countries, Schumacher (1973) viewed economic development and well-being from a “village perspective”, that is, through a regional approach. Schumacher pointed to the gulf between the employment infrastructure needs of urban settings and towns and villages. Schumacher’s village perspective draws on two interconnected factors: “enoughness” and sustainability. Counter to capitalistic continuous growth, maximum well-being comes from having enough for everyone. This viewpoint comes from the idea that bigger is not always better, from which emerges the philosophy of “Small is Beautiful”. More recently, the “15-minute city” philosophy draws on this village perspective approach; an urban planning concept coined by Carlos Moreno in 2016 that means essential (Moreno et al., 2021). It is not always possible in rural Wales, but it is an inspiring principle. Though somewhat contentious in the media, this concept of meeting our daily needs is particularly relevant to Wales and could turn the tide on the issue surrounding the ageing population by retaining our younger generation through good, local employment opportunities. The growth of social enterprises in Wales is one actor in this change by putting resources and job opportunities back into our communities, driving a different kind of prosperity with sustainability at its core. A key factor is, of course, relevant legislation, and devolution extended to Wales having law-making powers in 2011.

Wales has passed the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (see Figure 2 below), which makes it necessary for all policies and plans, national and local, to consider the impacts of actions taken now on future generations.

Figure 2. Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 infographic

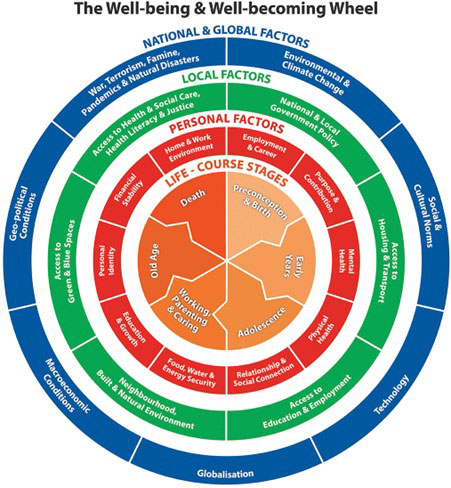

The Well-being and Well-becoming Wheel infographic (see Figure 3 below; Edwards, 2022), developed here in Wales, highlights the need for a life-course approach to prevention of avoidable ill-health, disability and premature mortality. Its rings highlight the vulnerability of all life-course stages to factors that are at risk due to climate change. The red inner ring highlights food and water security, education, good work and community. The blue outer ring highlights climate change and natural disasters, sometimes initiated or influenced by climate change, war and pandemics.

Figure 3. Well-being and Well-becoming Wheel infographic (Edwards, 2022)

This infographic reflects an underlying concept of “the wheel of life”. The first concentric ring is red and reflects personal factors that determine or have an impact through the life-course on well-being and well-becoming. These are: employment and career; purpose and contribution; mental health; physical health; relationship and social connection; food , water and energy security; education and growth; personal identity; financial stability, and home and work environment. The second concentric ring is green and reflects local factors that determine or have an impact on well-being and well-becoming through the life-course. These are: national and local government policy; access to housing and transport; access to education and employment; neighbourhood, built and natural environment; access to green and blue spaces; access to health and social care, health literacy and justice. The third concentric ring is blue and reflects national and global factors that determine or have an impact on well-being and well-becoming through the life-course. These are: environmental and climate change, social and cultural norms; technology; globalisation; macroeconomic conditions; geo-political conditions, and war, terrorism, famine, pandemics and natural disasters.

This infographic reflects an underlying concept of “the wheel of life”. The first concentric ring is red and reflects personal factors that determine or have an impact through the life-course on well-being and well-becoming. These are: employment and career; purpose and contribution; mental health; physical health; relationship and social connection; food , water and energy security; education and growth; personal identity; financial stability, and home and work environment. The second concentric ring is green and reflects local factors that determine or have an impact on well-being and well-becoming through the life-course. These are: national and local government policy; access to housing and transport; access to education and employment; neighbourhood, built and natural environment; access to green and blue spaces; access to health and social care, health literacy and justice. The third concentric ring is blue and reflects national and global factors that determine or have an impact on well-being and well-becoming through the life-course. These are: environmental and climate change, social and cultural norms; technology; globalisation; macroeconomic conditions; geo-political conditions, and war, terrorism, famine, pandemics and natural disasters.

Figure 4 below is experimental. Here we try to map climate change-related threats to health onto the traditional primary, secondary and tertiary definitions of prevention.

Figure 4. Prevention Triangle of the Effects of a Changing Climate on Health and Well-being

The need for cost-effective approaches to mitigating the health effects of climate change

The discipline of health economics, which studies how we traditionally have used scarce resources to meet our health care needs, is fast transitioning to embrace the way we use scarce resources through public health interventions to prevent avoidable ill-health, disability and premature mortality. It is now one of the academic disciplines that can help produce evidence of cost-effective ways to mitigate avoidable risks to population health of climate change. Here in Wales, the global challenges to tackle the risks of climate change need to be brought home to the likely impacts on communities at a local level, both urban and rural.

Figure 5 below lists a range of methodological tools that can be applied to evaluating the relative costs and benefits of interventions to mitigate potentially negative impacts of climate change, and factors affecting global health and ways of prioritising across these potential interventions.

Figure 5. Health economics as a contributor to cross-disciplinary research in health, well-being, sustainability and climate change

Health economics as a contributor to cross-disciplinary research in health, well-being, sustainability and climate change |

||

One Health/ One Health Economics

An approach calling for “the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally, to attain optimal health for people, animals and our environment…. The approach mobilises multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems, while addressing the collective need for clean water, energy and air, safe and nutritious food, taking action on climate change and contributing to sustainable development”. |

Health economics methods of analysis (in no particular order):

These methods can make use of:

|

Places of Climate Change Research Centre (PloCC)

Places of Climate Change (PloCC) is a collaborative research forum that unites perspectives from many disciplines at Bangor University. This allows academics, researchers, and PhD students to jointly address sense-of-place notions in relation to climate change. The notion of ‘place’ has long been recognised in human geography and other areas as a locational concept to which humans feel attached in some way (e.g., emotionally, culturally or through a sense of responsibility and ownership). Climate change happens globally but is felt locally, in the places where we live and to which we feel attached.

|

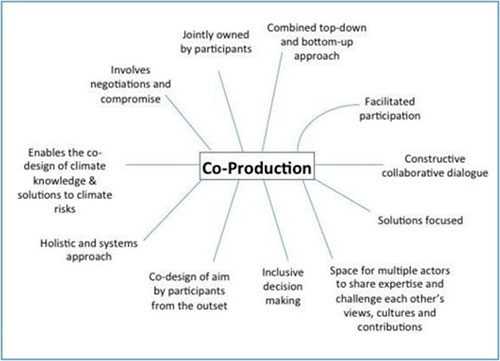

Just as in public health and preventative health care, there is a need for patients and health care systems to “co-produce” better health and prevent avoidable health problems, so this is the case with respect to the risks of climate change. For population health, there is an imperative for government, local communities and individuals to co-produce prevention of avoidable ill-health. Figure 6 below is perhaps a useful reminder of the multiple stakeholders and varying perspectives across policymakers, health and social care providers, local government, communities and individuals, all of whom will face health effects of climate change. They are all potential agents in cost-effective mitigation of such health effects from climate change here in Wales.

Figure 6. Characteristics of co-production from workshop deliberations (Howarth et al., 2023)

To conclude, Wales offers a microcosm as a small and beautiful nation where we can undertake research of policy relevance that can have far wider generalisability.

References

Edwards, R. T. (2022). Well-being and well-becoming through the life-course in public health economics research and policy: A new infographic. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1035260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1035260

Howarth, C., Lane, M., Morse-Jones, S., Brooks, K., & Viner, D. (2022). The ‘co’ in co-production of climate action: challenging boundaries within and between science, policy and practice. Global Environmental Change, 72, 102445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102445

Marmot, M. (2020). Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ, 368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m693

Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Roberts, M., Morgan, L., & Petchey, L. (2023, September). Children and the cost of living crisis in Wales: How children’s health and well-being are impacted and areas for action. Public Health Wales. https://phwwhocc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PHW-Children-and-cost-of-living-report-ENG.pdf

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Little, Brown Book Group.

UK Health Security Agency. (2024, January 15). Health effects of climate change in the UK: state of the evidence 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/659ff6a93308d200131fbe78/HECC-report-2023-overview.pdf

Victor, P. A. (2023). Escape from overshoot: Economics for a planet in peril. New Society Publishers.